I majored in philosophy and now work in tech.

I don’t think I would have been able to transition into tech without any of the skills I developed outside the classroom (such as learning to code & pursuing quite a few internships). In fact, compared to my peers who studied engineering, I’ve had to invest much more time outside the classroom in picking up technical concepts.

With that being said, I do think that my philosophy degree benefits me immensely with my day to day.

The three main benefits of my philosophy degree have been the following:

No matter what your role is, you’re going to be communicating with people. And in an increasingly remote world, the ability to express your ideas in a clear and concise manner is extremely valuable.

As a philosophy major, the emphasis was always on writing clearly. Unlike in other humanities classes I took, like sociology, our papers didn’t need to be very long.

The goal was to eliminate fluff and get straight to the point. For example, there was no need to introduce your argument with some sort of historical narrative or background information.

This approach lends itself well to the workplace. Think about long emails and unclear meeting agendas. The ability to parse out what matters and get rid of the rest will make you stand out.

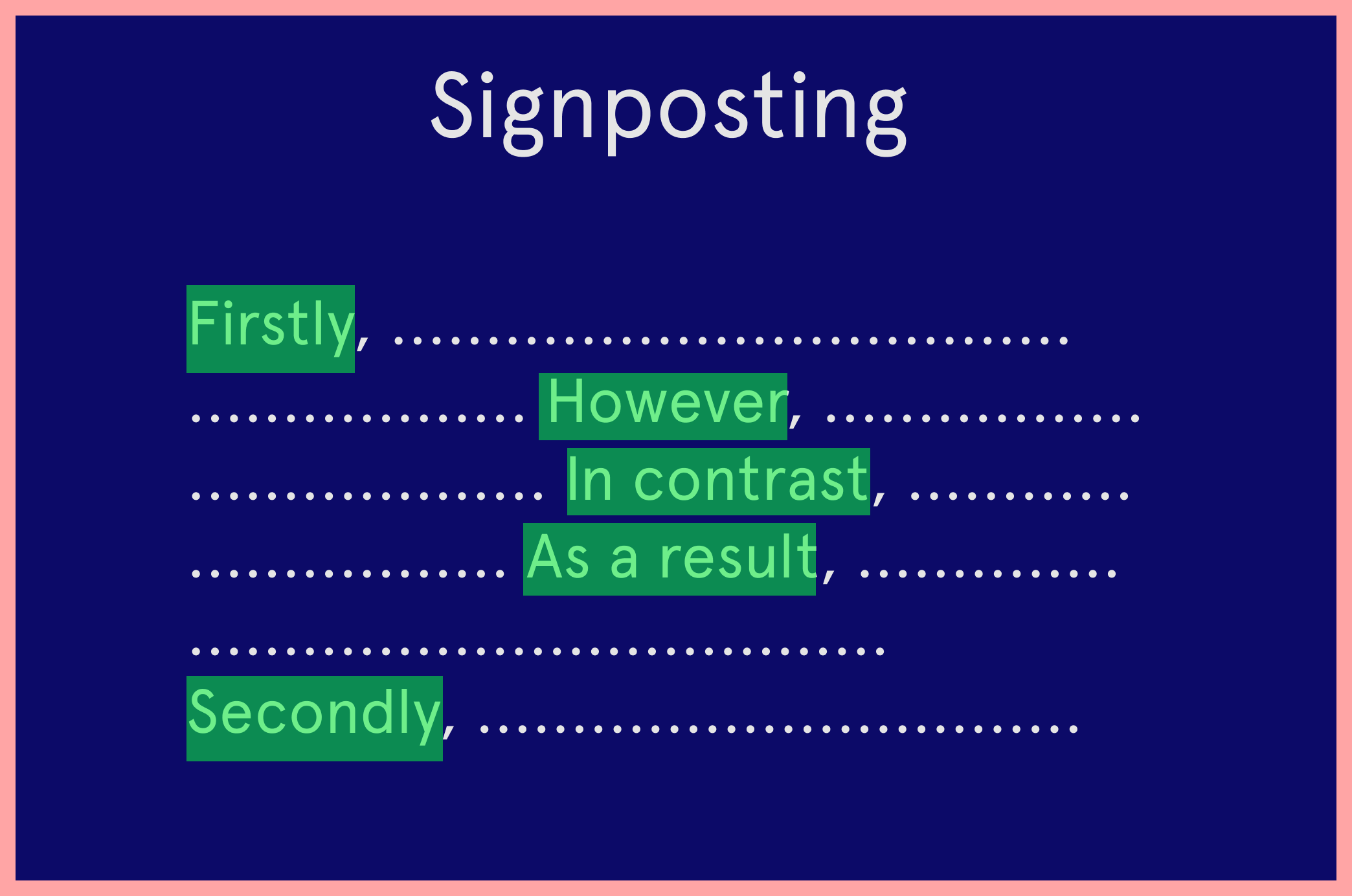

Another writing skill that my philosophy major taught me is “sign-posting”. This has to do with using certain phrases, such as “I will give two examples to prove...” or “My first objection is…”, in order to make sure that the reader knows where the argument is going at all times.

An added benefit of using sign-posting is that it enables the reader to skim your writing and still understand everything you’re trying to say. In web design, it’s often advised to ensure that your content is easy to skim by adding headings, sub-headings, images etc. Think of signposting as making your writing easier to parse.

Finally, I realized early on that a philosophy paper is never written in one go. It’s an iterative process that demands you create a clear outline and revise each part until you have a coherent argument.

Much of this revision process is better done by collaborating with other people. Reading your argument out loud will often make you realize that it doesn’t make sense. Or that it actually doesn’t get across what you’re trying to say.

I can’t tell you how many times reaching out to someone at work to read over something I wrote has been helpful. Getting a second pair of eyes can help identify flawed assumptions and tighten up documentation.

Philosophy is pretty similar to math in the sense that both fields require you to make assumptions and then investigate the consequences of those assumptions.

Unlike math, though, which is very narrow and technical, philosophy aims to solve problems that are very messy and fuzzy.

As a result, when investigating an open-ended question, it's a philosopher’s job to add as much precision as possible.

Let me give an example. I recently came across the case of a group of youngsters who were tried and sentenced in Kansas after a video tape of them torturing and burning a dog surfaced in the public.

Now, also note that many prominent criminal psychologists have long recognized cruelty to animals as a precursor to violence against humans. In other words, the likelihood of someone committing a crime against humans is considered to be higher if they’ve in the past committed animal cruelty.

So let’s go back to this case. It seems fairly obvious that the judge is going to sentence these youngsters to some time in prison. But wait a second - is he also going to take into account the fact that they are now potentially more likely to commit a crime against humans in the future? Or is he just going to sentence them for what they did?

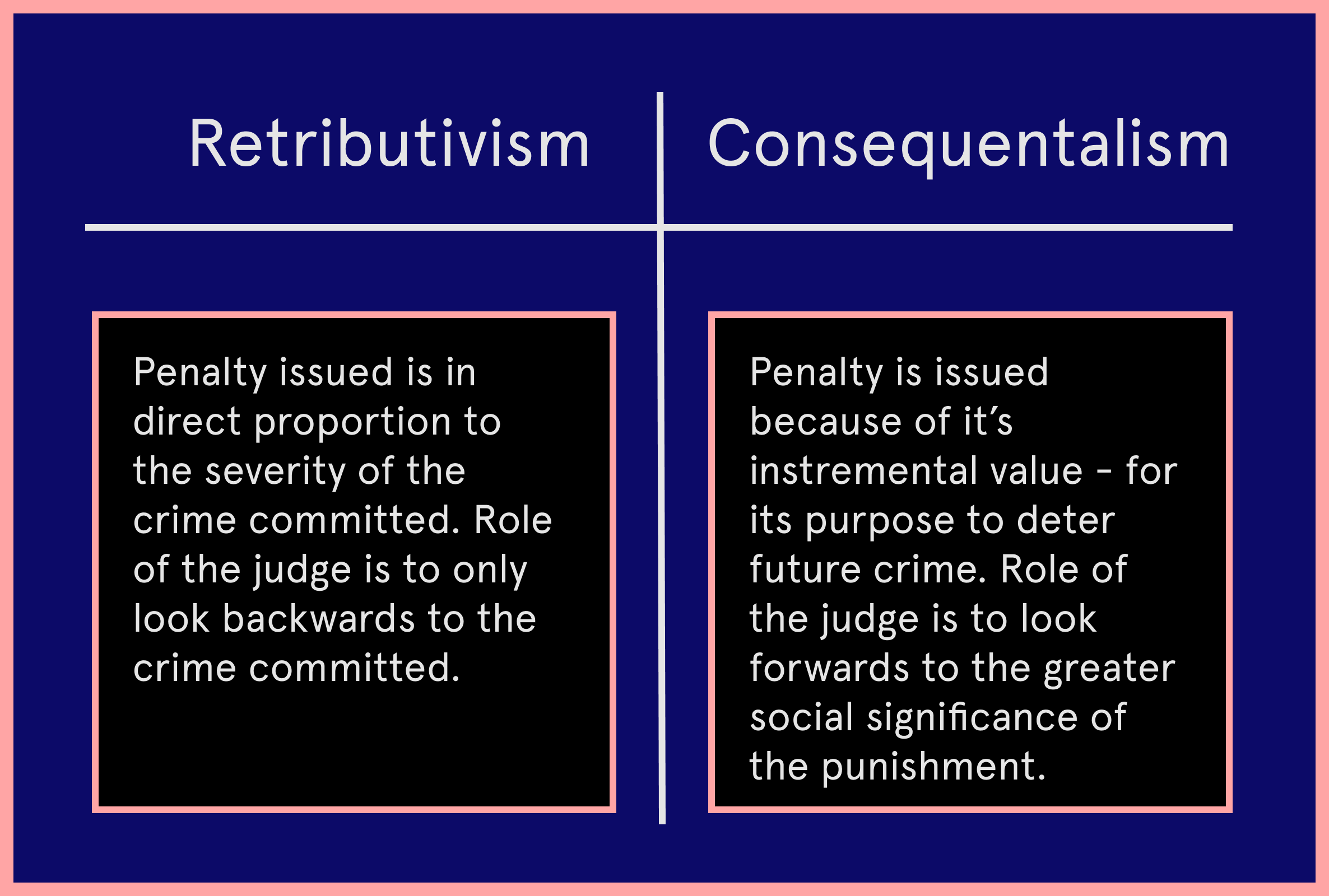

The distinction here is crucial. If the judge solely sentences the youngsters for what they did to the dog, then we can say that the judge is taking a retributivist view. By this, we mean that the judge is issuing a penalty that is in direct proportion to the magnitude of the crime committed.

But if the judge does decide to lengthen their sentence because he believes that there is a potential future risk of them hurting other humans, then he is taking a consequentialist view. Here, the judge is also punishing for a crime that has not yet been committed (but could potentially be) for the sake of securing a greater social good.

So the rather vague conclusion of “Youngsters sentenced to prison for hurting a dog” can actually be made much more specific by examining the two theories of retributivism and consequentialism.

A philosopher’s job is to make both sides of the argument crystal clear. And when there’s room for ambiguity (which is most of the time), his/her job is to fill in the gaps.

A practical application of the above in my day to day is when I need to understand what a client really wants. They’ll often be extremely vague about their requests and it is my job to capture the more important bits of information and then transfer that knowledge to my team.

Now, I obviously don’t have to deal with moral issues like the animal cruelty case above, but the exercise of critically evaluating the different pieces to an argument has come in very useful.

An argument is a group of statements including one or more premises and one and only one conclusion (source).

If you can identify a false premise, you can invalidate an argument.

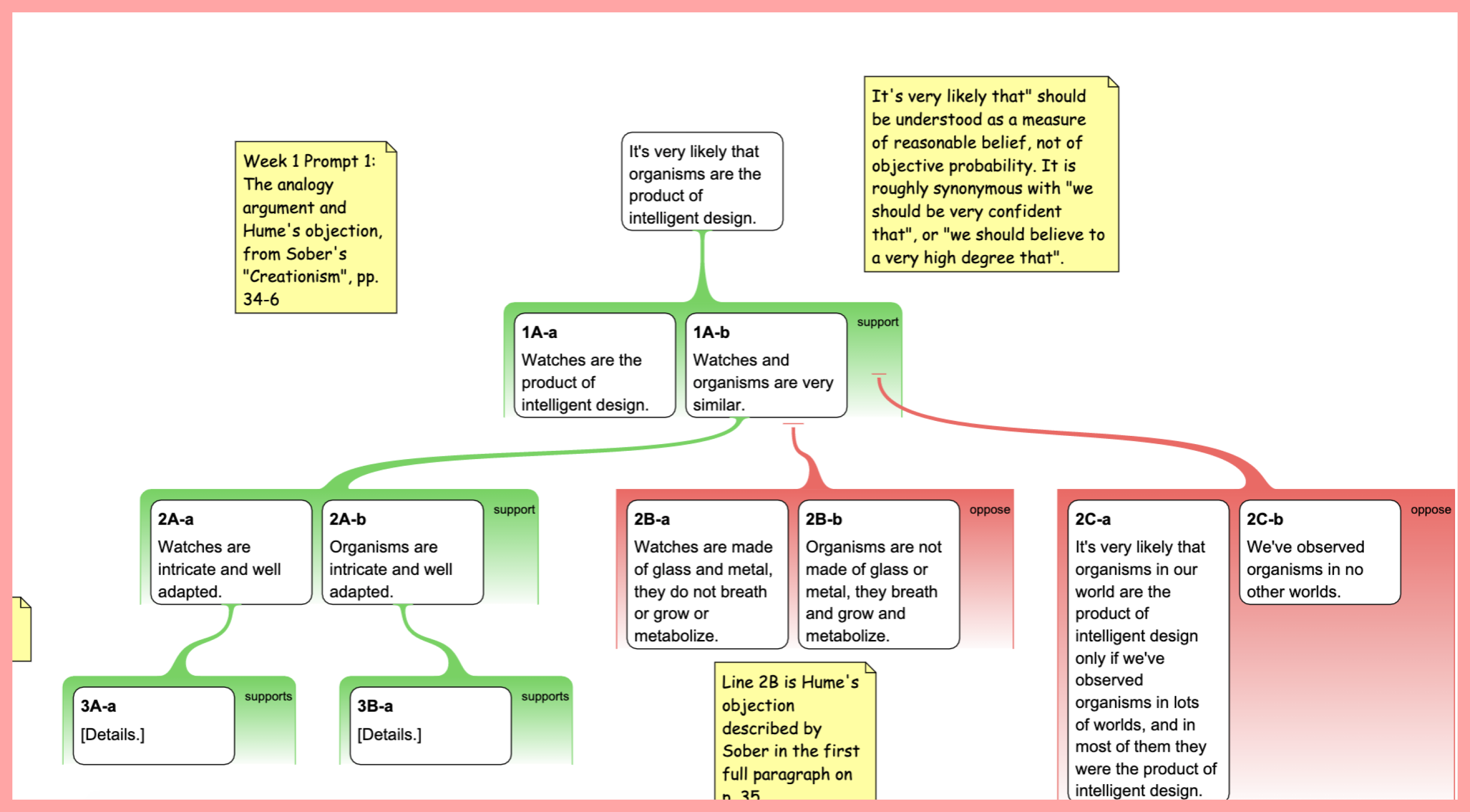

One of the ways in which I learnt how to do this is by argument mapping. One of my professors introduced us to a tool called Rationale that makes it really easy to do this. For example, here’s what an argument map for intelligent design might look like:

An argument map makes it very easy to follow an argument. My professor would always encourage us to create an argument map before we actually started writing our papers because it would make the writing process much simpler.

Instead of just stating why I think an argument is flawed, an argument map made it easy for me to point to exactly which premise I disagreed with and to present an objection (as can be seen with the red colored boxes).

Argument maps also make it easy to answer the question: “How does this sentence fit into the larger structure?” By visualizing statements that are used to support one another, I am able to understand their necessity.

Finally, argument mapping also helps with anticipating potential objections to my argument. Even though I could find my overall argument to be convincing, there would be certain premises that could be better worded.

The above is all very useful in my day to day. I’m able to comprehend, synthesize, and communicate information in a persuasive manner.. Whether it be in gathering approval from my team members to pursue a certain solution or crafting an email to a client to increase revenue, my ability to craft strong arguments comes in handy everyday.

There are certainly ways to get the above benefits without having studied philosophy. But I hope that my account has convinced you that philosophy, even when not pursued further in academia, can yield surprisingly practical benefits to whatever career you choose to pursue.

The ability to communicate well and to form clear arguments is useful in just about every field.

If you’re a philosophy major, you'll likely have to spend quite a bit of time outside the classroom picking up industry specific skills. But rather than playing “catch-up”, the combination of these newly acquired skills and the solid base that your philosophy degree has provided you with will make you even more valuable in the long-run.

Some people call it a newsletter - I call it a good time. I write about tech careers and how you can get ahead in yours. It’s my best content (like this case study) delivered to you once a week.