Anthony Chen is Employee #1 at Flexport. I spoke to him about what he was doing before joining the company, how he’s seen his role and responsibilities evolve, and what he’s learnt along his journey.

I was working in Venture Capital (at a firm called Signia Venture Partners) in the Bay Area. I was an associate sourcing deals and doing interesting research. Coincidentally, between investing in Flexport and another YC company, Signia went with the other company.

That other company was called Cruise, which got like a $2B exit in two and a half years, so that worked out well for them.

Before the startup world, I was on Wall Street doing Investment Banking.

So back then, startups weren’t as big a thing as they are now. I saw Finance as the fastest way to pay off my student loans. I’m from an immigrant family, so I paid for most of my education myself. And investment banking let me pay off everything very quickly, within the first 2-3 years.

As a result, though, I was nearly broke when I moved to Silicon Valley! So all that Wall Street money and bonus just went off to paying my student loans.

My background was in Computer Science and Business, so I was always interested in technology. In undergrad, I also spent a lot of time starting and running organisations - starting teams, growing teams, scaling teams etc. And my parents also ran small businesses growing up, so I did a lot of that as a kid.

International trade, freight forwarding, customs brokerage etc - it was all new to me, but because my dad used to receive cargo and stuff for his grocery store, it wasn’t completely left field.

The reason I joined after doing my due diligence was that a lot of the “goldilocks” ingredients were there. Ryan was a founder with two successful exits in adjacent industries. I had also done some research on unicorn startups and one of the commonalities was that most of the founders are in their early / mid thirties, have had a prior exit in a similar space, and are working on an enterprise company.

So Ryan checked a lot of those buckets. The freight forwarding industry itself was fairly stagnant and ripe for disruption. We were one of the first logistics technology companies to emerge and get funding, so we did something right and helped open the floodgates for plenty of other companies.

Finally, Ryan is a true entrepreneur and someone I wanted to learn from.

When your bank account is small, you have nothing to lose. The only risky thing was not doing anything. I think that the challenge here is that when you leave something that is kind of a prefixed journey (step 1, step 2, etc), a lot of your friends and colleagues are going to really question what you’re doing.

Your colleagues will see it as a ridiculous risk and wonder why you’re joining a no name company. But hopefully you’ll also have some good friends who are supportive of what you’re doing.

I think that when you do a startup or join one at an early stage, you definitely take on risk but you have to trust that no matter what you have to learn or do something. The rest is all upside.

On the flipside, though, when you do come out at the end of that tunnel and the company is doing really well, all of the friends who doubted you first are now saying it's amazing.

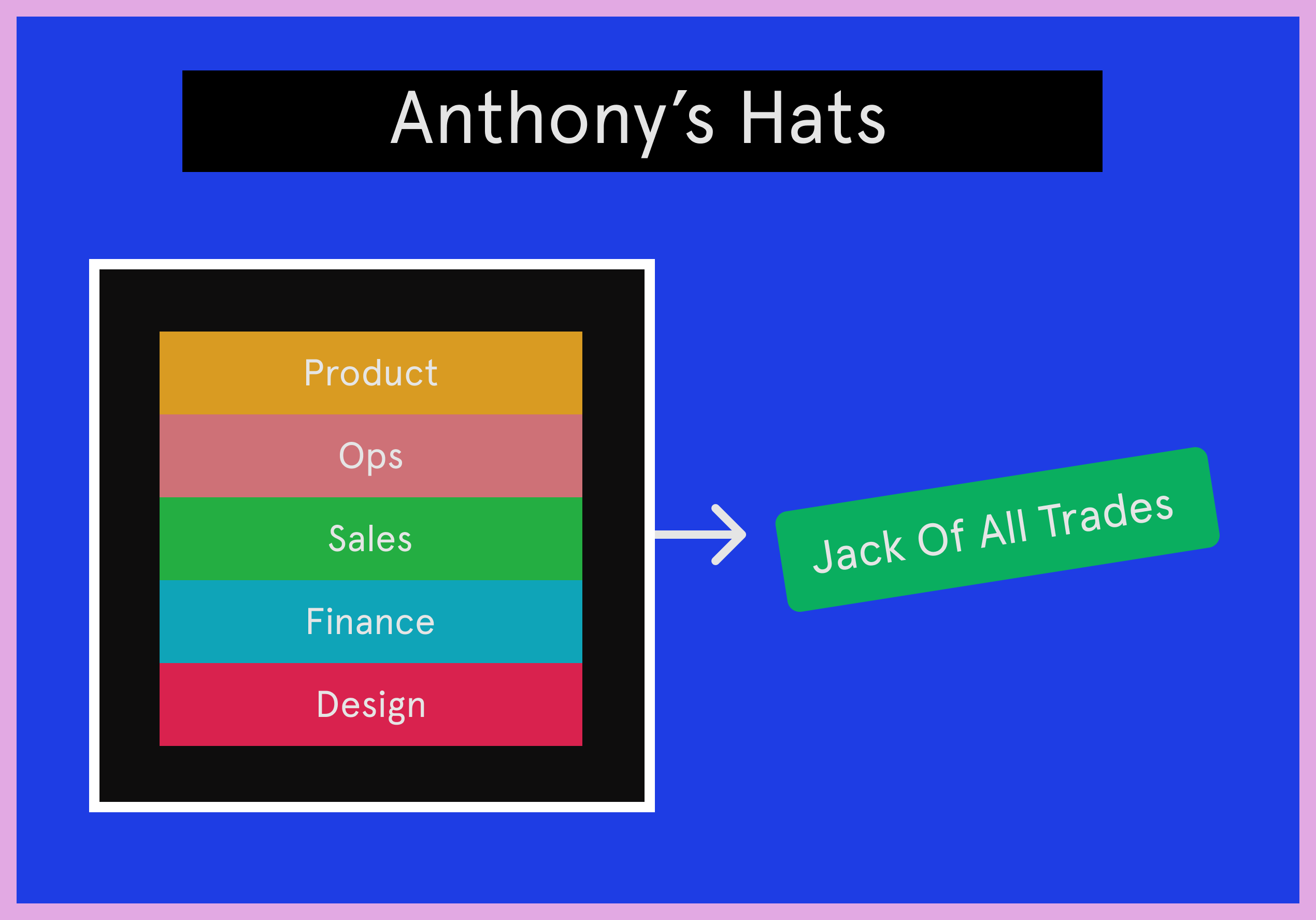

The actual job post that Ryan had was for a jack of all trades. Given my background in engineering, business, and a little bit of design, it seemed to resonate and work well. Mix that in with family entrepreneurial hustle, that also was well received.

And for folks who are looking to join an early stage startup, you have to have no ego and be willing to do anything and everything. My hats consisted of many things. I did ops, sales, finance, design and product.

But that’s not necessarily going to be the journey for everyone that joins an early stage startup.

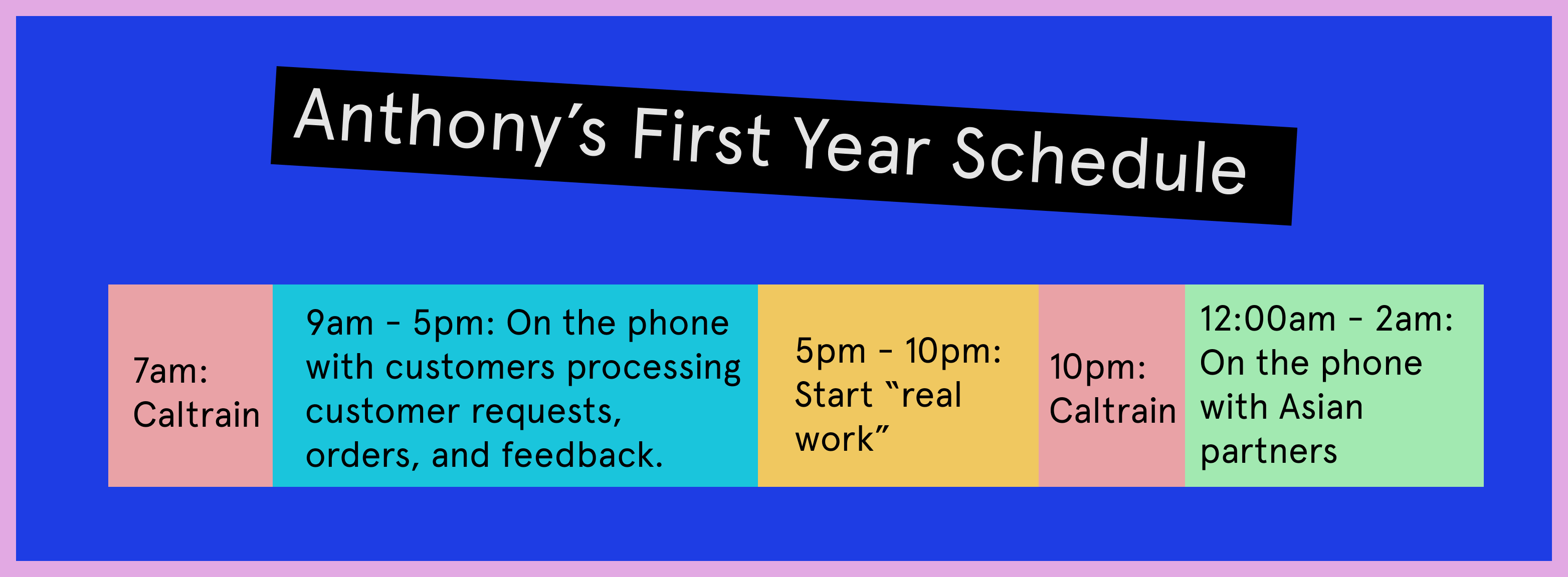

Everyday. So from 9am until 5pm, we’d have a call every 10 or so minutes. Which means that the entire day we’d basically just be processing these customer requests, feedbacks, orders etc. And then we’d actually start the “real work” from 5pm to 10pm, or until later.

The first year was very aggressive. I lived in Palo Alto at the time so I would be on the CalTrain by 7am, in the office in downtown SF by like 8:30, and then we’d work until 5 or 6, have dinner, and then work until around 10 again.

Then, I’d take the CalTrain back to Palo Alto anywhere between 9pm to 11pm, get home, and work from 12 to 2 again. It was crazy because I had to work two shifts since we had both US clients and Asian partners. So when night came, Asia would wake up, and I’d need to be on the phone with our partners, factories, etc over there.

What was hilarious was that I’d be talking to the Chinese factory until like 2am or 3am in the morning, and they’d be like “Oh, are you getting ready to get off work?” and I was like “No, I’m going to go to sleep”.

The big picture scale was always apparent. Our trojan horse was customs, and that was the core business for a period of time. We never thought that the business would explode so quickly in terms of scope in the way that it did - that was serendipitous. A lot of it was just down to the fact that success compounds and we had tons of momentum behind us.

To answer your question more directly - since we were on the phone all day with our customers, we got to know their pain points really well. What were they scared of? What sucked for them? These were questions that were really easy for us to answer.

More generally, most people don’t like to be uncomfortable. People don’t like pain. But you need it. If you actually want to find out what problem needs solving, you need to feel the pain. If you don’t feel the pain, you’re not going to build the right thing and you’re not going to be able to fix it.

You’re going to be working from an ivory tower and being all theoretical. So the feedback that we got over the first 3-4 months was overwhelming: our customers felt like their freight partners were often mismanaged their shipments, communicated poorly, coordinated poorly, and lacked accountability. No managed service... We wanted to step up and help.

And so it was around Month 6 when we took the phones off so that we had time to think. We started to re-evaluate what we were doing for our customers and how we could make their pain go away. And that’s what led us to freight forwarding, because that’s what would allow our customers to have control right from the beginning to the end. Rather than only providing US Customs clearance services.

I think when we did our first few shipments we realized that we just added a zero at the end of our business, like a 10x multiplier, because freight forwarding is a much larger market than just doing the customs stuff.

I think the majority of the early stage clients were mom and pop shops. Majority of them were just companies that were googling customs clearance and trying to look for someone to save their ass. And so usually, that didn’t make for the easiest of customer problems, but it definitely showed us what was painful.

To be honest, when we were more deliberate about the types of customers that we wanted to work with, we wanted to find people that were philosophically aligned with us. I think that’s true for any partnership you should do as a business. And when we started doing that, we started to find customers who were growing much faster and wanted to work with us. So as you can imagine, a lot of startups and bay area companies resonated with our vision: "to make global trade easy for everyone".

These customers were much more helpful in providing proper feedback, referrals, and overall that philosophical alignment helped us land much bigger accounts (which we otherwise would not have been able to).

Oftentimes, many of the “long tail” or smaller companies get ignored by the bigger companies. Even though DHL and Fedex are known for their last mile fulfillment, they have huge freight forward operations as well, but it doesn’t make sense for them to go after these customers. They have a lot of fixed costs, onboarding costs, and client education needed.

So we saw that as an opportunity. Because if we built software to automate onboarding and get rid of a lot of those fixed costs, it would make sense to go after those smaller accounts.

But yeah, these customers were really being ignored. And that’s why they were more than willing to try a new company like ours out.

Yeah, many of those rapid changes were a lot of fun and got to really test your mettle. I think the first few years it was a lot about turning the individual into institutional, reflecting about what was working and what wasn’t.

So, very systematically, every 2 weeks we had workshops that I led to figure out where the holes were in our process. We were very intentional about this - we didn’t wait for an account exec or an ops teammate to slowly bubble problems up. We were still small, still lean, and our DNA said we want to solve problems.

Everyone on the team felt like they were a true product owner and they were solving problems for the business that went beyond just their job title. Everybody was contributing to how we could improve the process and product.

Yeah, it was very deliberate. We wanted to have a good mix between experienced industry knowledge, experienced tech knowledge, and then the generalist problem solvers. By combining these 3 types of personas together, you created a very strong culture and also a dynamic that allows your team to ask questions like “Hey, why isn’t this tech possible?” or “Hey, why didn’t the incumbents do something like this before?”.

And that was very powerful. It made our feedback loop remarkably fast and agile.

That is an ever changing problem with an ever changing solution. So I don’t have a perfect answer for you. What I can say, it’s probably one of the biggest topics that every company will always need to keep on top of mind.

Values stem from people. Things like hiring, managing, and coaching. All those elements are important and you need to be intentional about how you do each of those things. For example, are you looking for people that demonstrate these attributes we’ve communicated? Also, are you instilling the right positive feedback loop when they’re being trained? Do they see that in practice? And then, do you lead or have managers that embody this as well?

In regards to scaling this, it’s hard. But in my opinion it just needs a real human touch. You are able to scale culture by having strong culture carriers and ultimately that means you need to have strong managers. I think having strong individual culture carriers is great, but if you have a manager that is a strong culture carrier, and they’re able to recruit, manage, and lead, then that’s a huge multiplier and you have a 1 to N dynamic.

I think when you don’t invest in your management, you see the consequences of weak culture, poor morale, and short term thinking. And by the way, I think what a lot of people don’t realize is that investing in your managers doesn’t mean just giving them a short 1 week training and tell them to go fight fires and solve all your problems.. It means that as their direct report, you spend time with them. It means that even though they may have all these fires to put out, you still give them some buffer that they need to reflect and internalize. It means giving the room to grow and improve. And a lot of companies have a hard time doing that because it’s at odds with getting shit done now. It’s hard!

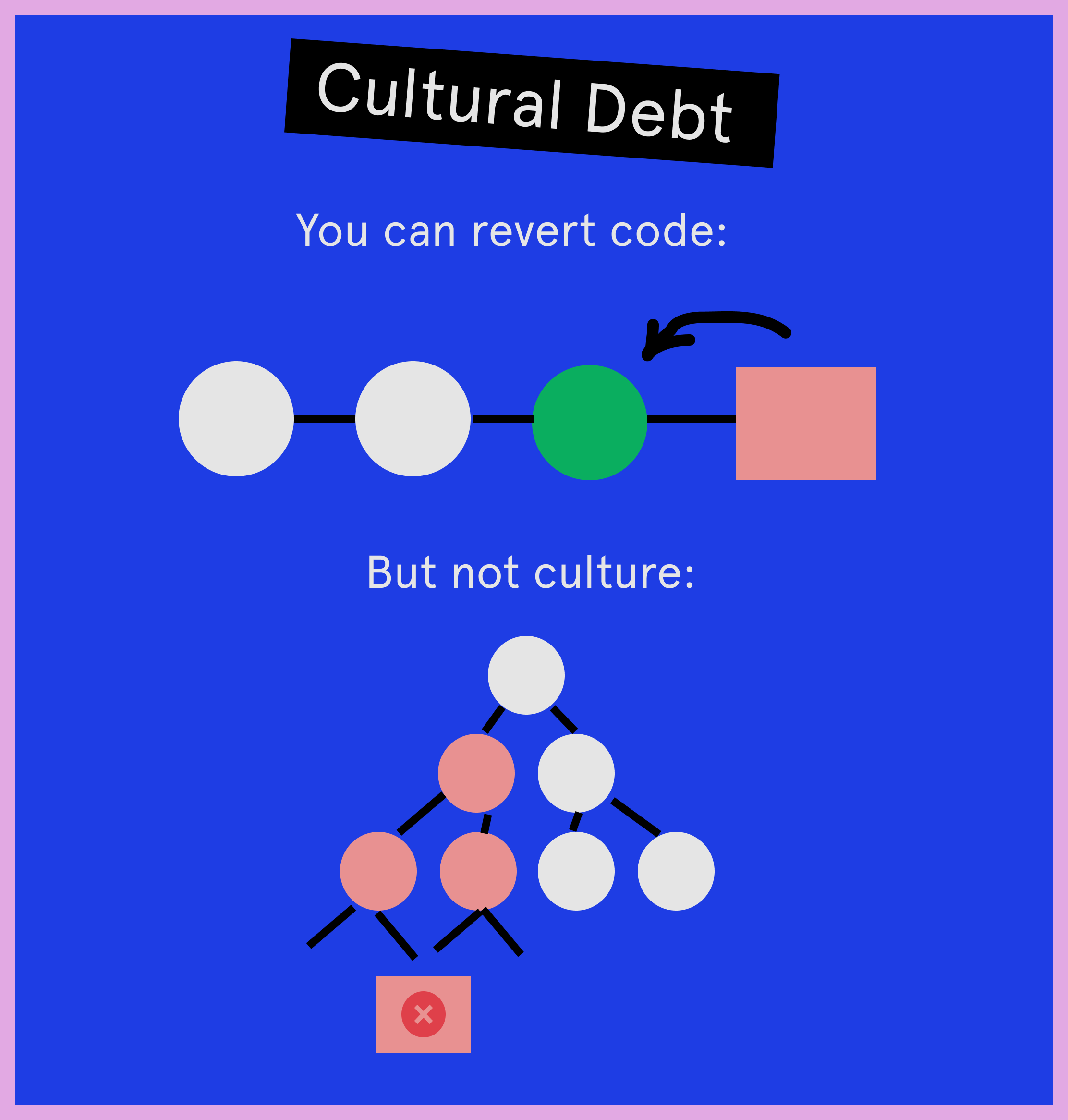

Exactly and you’ve probably heard of the term technical debt, but cultural debt is much more expensive. With technical problems, there’s pretty much always a solution. But with culture and people, it’s not so cut and dry. You have to factor in the EQ and all of a sudden it’s much harder than the technical challenges.

You can revert code, but you can’t revert culture.

Make it so that your decision is a win-win no matter what happens. And if you feel like your decision is going to be a win-win no matter what happens, then go for it. Because you’re going to be jittery about joining a new company, you’re going to weigh the pros and cons, think about what the opportunity costs is, etc - and all of that is true.

But what I mean by "make it win-win", is that you're able to make the best of the situation regardless of whether the company crushes it or has to fold. If the company does well, then great, you're in a win scenario. But what if, for some reason it fails? Do you still feel like you'd be able to pick up new skills? Learn from your leaders and colleagues? Push your comfort zone? And become more tempered? If so, then you've found a win-win scenario.

I’m a light-weight angel investor, but I love working with founders and helping them navigate that seed to late Series A / early B stage. I enjoy helping them figure out how to hire, grow, and build. And ultimately, set up the infrastructure needed to get scaling ready and in place. By no means am I an expert in all these things, but I think for the Seed to Series B stage, my insights are helpful for a lot of entrepreneurs. I love working on those challenges.

***

Hope you guys enjoyed that interview! You can connect with Anthony on Linkedin here.

If you want to read more Employee #1 interviews, check out this one with Yash Nelapati of Pinterest and this one with Micah Bennett of Zapier.

Some people call it a newsletter - I call it a good time. I write about tech careers and how you can get ahead in yours. It’s my best content (like this case study) delivered to you once a week.